estimated reading time 12 minutes

Kampala & Berlin, in June and July 2021

Dear Passenger,

shortly before departure I received an email from Air Ethiopia. The usual announcements, information on hazardous substances and permitted weights, or a less attractive offer for an upgrade to business class, I thought to myself and ignored the letter. Uganda has been classified as a risk area and travellers from regions where the delta variants of Sars Cov II virus occur are not exactly the most sought-after guests. Rwanda and the United Arab Emirates had already imposed a ban on all flights from Uganda in mid-June. A stay in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, I had cancelled shortly after entering Uganda, so there could be no nasty surprises in this regard – hm, even then – I fished the email from the trash folder: Bingo! Bonus! Again, Air Ethiopia gave me time. My flight on July 17 in three stages from Entebbe to Berlin would start earlier than scheduled, but the stay at the airport in Addis Ababa was extended to eight hours and forty minutes. I jubilated in anticipation! First, I would inspect how far the construction site of the toilets had progressed over the past few weeks. Would the reinforcement bars still stick up in the air like antennas receiving radio signals from another world?

I wondered if I would meet women again, whose bodies – tired from the long wait – stretched out on the floor between the rows of seats in the hall merged with their luggage to breathing living sculptures that made me think of driftwood which is washed to the shore by the current of the water. My eyes had found shoes, hardly any of which could be identified with their owner, scattered or in pairs they were drifting on the polished surface, floundering along the edges of the chairs.

This is how it had been six weeks ago, when my stay in the transit area of Bole International Airport had unexpectedly stretched to fourteen hours.

‘I STILL HAVE THAT DREAM’, Rose had said.

Her hands dipped into the water of the plastic basins and buckets she had arranged in front of her: the washing soap she had rubbed into the garments in particularly dirt-sensitive places, at seams and hems, foamed between fabrics. She worked the textiles with vigorous movements, wringing out T-shirts, jumpers, dresses, trousers, blouses over the different tubs – first the dirty, then the clarifying water. ‘It is my routine. I did the washing when I was a child, and I am used to it.’

She was still a child when, as the eldest in the row of seven siblings, the task of looking after the family’s laundry fell to her.

‚There is no other option apart of my hand.‘

Rose’s dream is to open a big restaurant.

‘The women at the airport you are talking about, were they wearing anything special?’ Beatrice Lamwaka asked me when we met for the first time in Kampala. Our encounter as scholarship holders in the artists’ village of Schöppingen in Münsterland goes back more than two years. Now we were sitting together in the garden of the guest house in Kampala. ‘Some wore purple dresses, and their hair was hidden under ochre-yellow scarves. Others were dressed in black, and the colour of their shawls was blue. Those on whose clothes golden letters entwined the lying eight and formed the lettering ‘infinity’ were flying to Saudi Arabia. Others waited at the gate for the plane to Dubai. Amaziha’s blackberry-coloured T-shirt read ‘Move -Jobs abroad’. We don’t know what to expect,’ she had told me when we started talking at a mobile phone charging station. The economic situation in Uganda and the hardship of her family had encouraged her to be recruited by an agency.

Amaziha had hired herself out as a ‘maid’ for two years.

A ‘maid’ is a modern-day slave – not every woman survives the cozen promise of wealth. Many are abused and raped. Many never return. Multiple testimonies of the women’s fate can be read. ‘Men in Uganda,’ Amaziha had added, “leave the work to the women.’ That is why she would have chosen to leave. ‘We have to work hard.’

The heartbeats off the sleeping. The shoes stripped off. The steps into the unknown:

‘All labour is measured in heartbeats – the monetary unit of the future, which every living human being possesses equally. ‘[1]

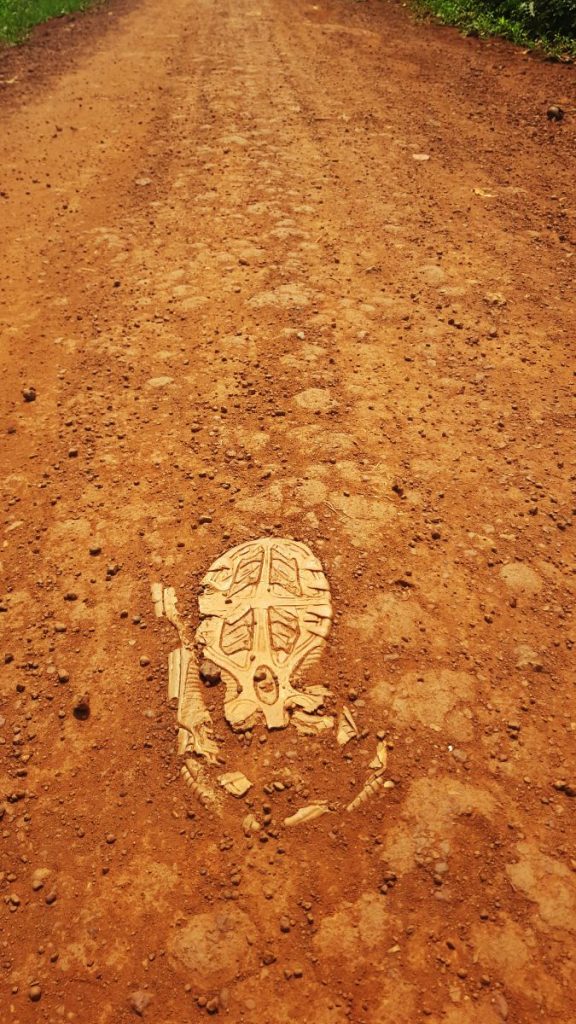

I WALKED ON THE BACK OF THE ELEPHANT

He had carried me in all directions, on the red ground with furrows, brittle lines and cracks.

The freshly washed laundry, spread out to dry on the lawn, draped over hedges and fences, sun-drenched on clotheslines, showed me the way.

The first house on the right, when you have walked the three-quarters of an hour from the town of Mpigi towards Sina Village and have almost reached the sustainable model village with its Social Innovative Academy, is inhabited by Helen and Jack and their children.

Helen was bent over a small cooking stove in the shade of a mango tree. Steam was coming out of the pot, probably she prepared beans, or porridge from posho. The laundry hung on the lines and divided the yard into segments. It was ten o’clock in the morning.

b: Helen, how often do you wash?

Helen, thinks about it and carefully counts down the days:

Every four days

b: Do you have a certain time when you wash?

H.: In the morning....

B: How long does it take you to do a load like this?

(Two washing lines, about six metres long, with bed linen and everyday clothes of the family)

H: Four hours

b: That means you start at 6 o’clock in the morning?

H:Yes.

(laughs)

b: How does your body react on the clothes washing procedure?

H: It exhausts me. But what should I do? I must keep going.

b: What do you think about when you do the laundry?

H: Even when I am doing the laundry, I think about something….

Sometimes I think about what to cook–

I think about the children–

About money too –

And how we will survive. –

Survival. No one knows how this will work – in case the lockdown will be extended at the end of the month, possibly beyond the 42 days.

LOOK BACK

‚For you, nothing changes‘ – Rose had said the morning after the President spoke out.

‘Just as you have walked up to now, you will continue to walk.’ The presidential speech had been announced for Saturday evening, June 19, eight o’clock. Karen’s little black Nokia was between our plates, and we listened to the – for inexperienced listeners like me – astonishing presentations and rhetorical excursions by President Museveni on the development of the pandemic. My journey began when the second lockdown came into force in Uganda. Now, after ten days, there was great fear among the people of further action. Therefore…. We were waiting for the keyword, which would precisely name the measures and regulations that the government would derive from the exponentially increasing number of infections and the overloaded health system. After 40 minutes at the earliest, Karen had prophesied, and reality would surpass her prediction. We had long swallowed the last spoonful of Posho – a kind of snow-white polenta made from very fine cornmeal – when we flinched after 75 minutes – the President said what people had suspected and feared: tightened lockdown with immediate effect.

At nightfall, I had crawled up the embankment at my junction from the Northern Bypass – in Berlin one would speak of the city highway – and had noticed with unease the array of pickup trucks with armed police officers. The cordon blocks placed during the day by the law enforcers at traffic-relevant points on the bypass turned out to be preparations for the implementation of the most serious restriction in the presidential catalogue of measures:

The ban of all public and private transport – no buses, no matatus (minibuses), no Uber’s, no Boda Bodas (motorbike taxis). Curfew from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m..

Since then, many people have not been able to get to their jobs – with disastrous consequences for their very existence.

The art of walking is not for survival.

We were three women, whom the President’s speech brought together at the table for an hour and a half for different reasons: Karen, born and raised in Kampala, a media woman and producer who lived in the so-called garden house in Bukoto when she had work downtown. She was stranded and couldn’t get back to her Mukono neighbourhood. Alex, who was doing an internship abroad, and me.

They can’t close the shops, Eria had prophesied. We live from hand to mouth. No one has the money to stock up for a week.

Eria, who looked after and guarded the house, was to be proved right. Food markets and retail shops remained open, while the shopping malls and commercial centres closed. The president advised the traders and vendors to spend the night in their market stalls if they could not make their way home without public transport. The government promised mosquito nets and umbrella….

I wondered how people would survive in the markets during 42 days of lockdown without showers and barely usable toilets.

I walked on, following the pieces of laundry, the freshly washed ones on the meadows, the piles of second-hand clothes on the roadside. I exchanged glances with the flying traders. Their arms served as presentation aid for their modest selection of shirts or trousers.Finally, I reached the halls, where bales of second-hand clothes from Europe, the USA and Japan were piled up.

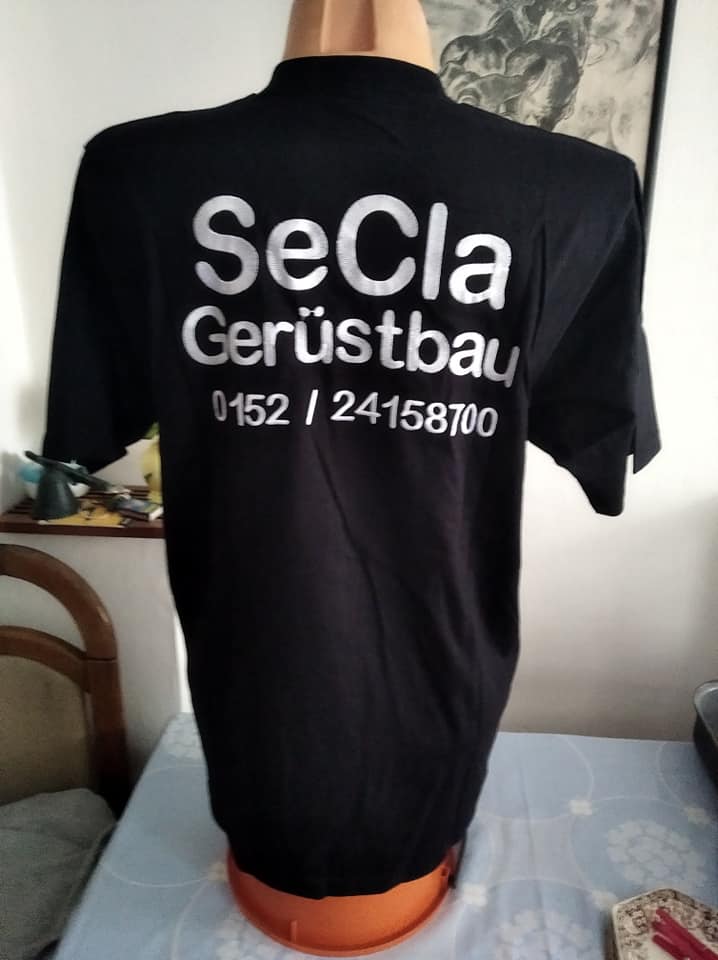

I bought a few T-shirts at the market in Kalerwe: A light green Adidas shirt, a shirt that says ‘Straight Outta Kindergarten’ and another one, advertising for ‘SeCla Gerüstbau’ in embroidered lettering, including a German mobile phone number. The construction company’s lettering stretches white on black across the entire back of the shirt.

In the modest wooden shack that served Charity and her children both as a salesroom and a place to live, a few blouses and dresses hung on a string: I opted for a pair of baggy silk trousers with animal print from Victoria Secret and a white T-shirt with the likeness of a rabbit in sequins of a Japanese brand.

My thoughts wandered along the seams that the tailors stitched into the fabrics with their pedal-powered Singer sewing machines. Like Winnie, who had been working from home since the lockdown. She presented her work on the trees in the garden of the house where she shared half a room with her two children. Only at night the electricity flowed – as agreed in her rental contract – then she would work on an electric sewing machine. During the day, she could be seen pedalling on the black Singer in front of the house. The machine is a jewel: black with golden lettering and curved ornaments – the machine is an inheritance of British colonialism: the colonial past has seamlessly carried over into the postcolonial modernity. The second-hand clothes flooding Uganda and their resulting socioeconomic consequences damage the country and its local textile industry and manufacturers – which, without electricity, will never be able to compete with the international textile industry.

“Is this second-hand clothing vintage or violence?” – In a six-part podcast series, designer Bobby Kolade and filmmaker and visual artist Nikissi Serumaga look at the flotsam and jetsam that is flooding Uganda’s markets through the overproduction of clothing and fast fashion – Uganda, just one African marketplace among others.

I thought back to the women at Addis Ababa airport who had swapped their clothes into a uniform, their scattered shoes seemingly of lost identity and threatened that the cleaning staff would sweep them away on the next round.

It was the tailor Harriet with whom I first tried to visualise in textile terms this clash between imported second-hand garments -Mivumba- and local production and fabrication. Harriet handed over to her daughter Ruth, who had just finished her last semester in fashion design at the YMCA Comprehensive Institute before the second lockdown….

We had fun. We exchanged associations and images and merged them in fabrics together. The rabbit is no longer grinning from the bosom area of a T-shirt from Japan but is sitting fat on the butt of a dress that fuses a traditional cut with a dressing gown in animal print from Victoria Secret, a flannel shirt from Germany, a pyjama with peace signs and a Nike shirt. Blood flood. Vintage or Violence.

Bood flood. Vintage or Violence.

Rose and Eria, who together run the guest house in the Bukoto district of Kampala where I have felt at home for the past five weeks, have embroidered excerpts from the conversation with Rose about the matter of washing on a bed sheet. It is the first in a series of hand-embroidered linen reflecting the thoughts of the ‘washerwomen’. Author Beatrice Lamwaka will oversee the further realisation in Kampala. The curse and blessing of washing clothes by hand is indeed a theme among Kampala’s contemporary writers.

The exchange about how we dress and wash, what we wear, about guilt, destruction and reconciliation, about colonialism then and now, about Christianity and the question why first names like Peter and Paul, Jim, James, Beatrice, Charity, Joy and Peace dominate over African first names accompanied the creation of a small collection of garments in collaborative work with Rose Faith Naalule and Sylvia Naatabi / Suubi design.

The top themes of my stay were ‘the bride price’, ‘the washing machine as utopia’ and the leitmotif stated by Rose:

I STILL HAVE THAT DREAM

Prêt-à-porter: STREETWARE x Mivumba | Photoshoot July, 13, 2021 | Kampala | ©Jim Joel Nyakaana

Kampala 2021

Also read CMP – The Colonial Matrix of Power

Within the Artists’ Contacts Programme of the ifa -Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations. Special Thanks to femrite uganda.

[1] The proposal for this labour reform was drafted by the Russian artist Velinir Chlebnikov at the turn of the 20th century. (Veinir Chlebnikov, Werke 2 , Prosa Schriften Briefe | Hrsg. Peter Urban | das neue buch rowohlt | 1972 )