Installationsansicht finalmeals, Kunsthalle Mannheim 2004©Kathrin Schwab

MEMENTO MORI VICE VERSA

by Michaela Nolte Berlin, October 2002, translated by Oliver Mechatie

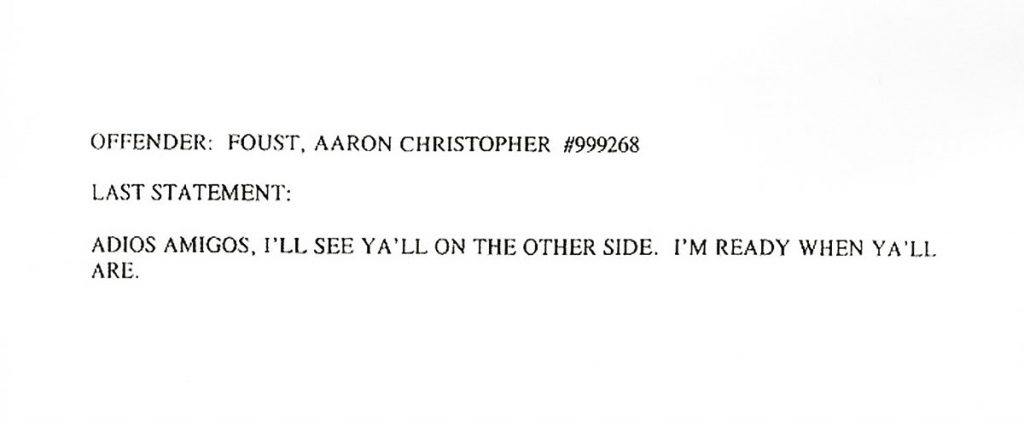

She looks into the camera angrily and with wrath: Betty Lou Beets, 48 years old, charged with the murder of her fourth and fifth husband. Police mugshots are in any case seldom charming, but one can believe without great hesitation that this woman committed spousal murder twice. That is if not there next to the protocol of the prison administrationit wasn’t for an illuminated box with the picture of a plastic tablecloth in an old-fashioned design, which evokes both an oppressive and moving emptiness. Betty did not have a wish, or rather not a last wish. She was executed completely sober on the 24 th of February 2000 with an injection.

Barbara Caveng has composed a laboratory out of the final meals requests of 16 executed people that makes the last meal a still requiem for the aggressors as well as for the victims. Each description of the delinquent and his or her acts is coordinated with a photograph, which in the form of a still life shows the last meal the executed person ordered. Caveng draws upon an art historical tradition which ranges from the many-faceted representations of Christ’s last meal to the still lives of the 17 th century to Viennese Actionism, in which the ritualistic use of animal flesh in the 1960s managed to break one of the last of society’s taboos. Though “Final Meals” reminds one methodically of the archive of Christian Boltanski and abstains from the concrete materiality of foodstuffs and raw metaphors, the direct meeting of the culinary and exitus evocates something which also goes against today’s customs of good taste.

©ralf grömminger

The Milanese Mannerist Guiseppe Arcimboldo created in the 16h century his beautiful and frightening portraits of people from fruits, vegetables and animals. Caveng does not anthropomorphizes edibles. However, in the sense of Ludwig Feuerbach’s winged words “Man is, what he eats”, the photographs become fictitious documents, in which the dramatis personae of the murderer as well as the one murdered undoubtedly take on a physical presence. The reality of the actions and the fiction of the pictures merge in a completely new pictorial reality, which compels the questions of guilt, lust and atonement in the audacious discrepancy between food and the protocol of death to reach a bitterly ironic high point.

In a space of 80 square meters the identically large and colourful illuminated boxes with the sober biographies in black and white are arranged in equal distance from one another. The symmetrical order and the dispassionate air of the installation remind one of the spatial and formal explorations of minimalist art. Caveng refers to the stylistic clarity of minimalist art, emphasizes this clarity in the neutral grey colouring and goes beyond the merely formal in her recourse to a quasi abstract reality. Pretty coverings with cornflakes and jars of milk or a strawberry shake served on a folded napkin with a piece of cheesecake in the face of a robbery-murder; several course menus which strike one as hedonistic flanking sexual murder. Even the claustrophobic narrowness of Bruce Nauman’s “Corridors” seems in comparison to the course through this death-wing comparably pleasant. The visitor, standing besides the seemingly harmless still lives and the bureaucratic protocols of execution, becomes him- or herself for a moment the “dead man walking”. The cells for prisoners on death’s row in US American prisons measure four square meters, and Caveng makes the narrowness of a life staring in the face of death, the life of the convict as well as that of the victim, corporally perceptible. The actual artistic space offers as it were a shelter in which, in dialogue with the horror of both the murderous acts as well as with the institutionalised machinery of death, the original self is suddenly mirrored.

A shiny green apple before a glimmering background accompanies the report on Russel James. At the age of 23 the black musician was sentenced to 50 years in prison for a robbery. Three years later he was found guilty of shooting a witness of the original crime in a forest while he was out on a free pass. The illuminated box brings prejudices and hasty judgments into question. The apple, just fallen from the tree of knowledge, seems innocent and paradisiacal. It is an artistically perfect tableau which is beautiful to see.

The arrangements in the photographs emanate the ingenuous charm of home-ed cookbooks from the 1960s. The meals, smartly and painstakingly set up, conjure up a simple and orderly existence. Thereby each of the chronicles ends with death – exactly as in normal life. Caveng does not visualize the desires and enjoyment of culinary pleasures in the way that is particular to classic still-lives, which awake in nature morte a sublime memento mori. This memento mori has been taken over by the seductive power of photography and in particular of commercial photography. Indeed the compositions appear at first glance appetizing and quaintly nice; however the formal severity and the frigidness of the photographs refer with their simple attributes to the social origins of the aggressor as well. It is precisely the identity giving aspect of foodstuffs and the component of the maintenance of biological bodily functions which are evoked in the cerebral moment between the humane gesture and the act of execution, the profound humanistic breakdown.

Even if there are those who would reproach the artist, with the colourful pictures right next to the raven-black facts, with a particular kind of cynicism, so is this cynicism surpassed by reality itself. Larry Wayne White requested with his liver and onions, cottage cheese and tomatoes a last cigarette. However in death row cigarettes are legally forbidden: smoking is a hazard to your health. Delbert Boyd Teague jr. ate before his execution a hamburger only at the urging of his mother. Not even taking the debates in America over executions as public media events into consideration, the absurd antagonism between the last caring gesture and the consciously induced death evokes a place of silence which makes the onlooker choke on the proverbial frog in his or her throat.

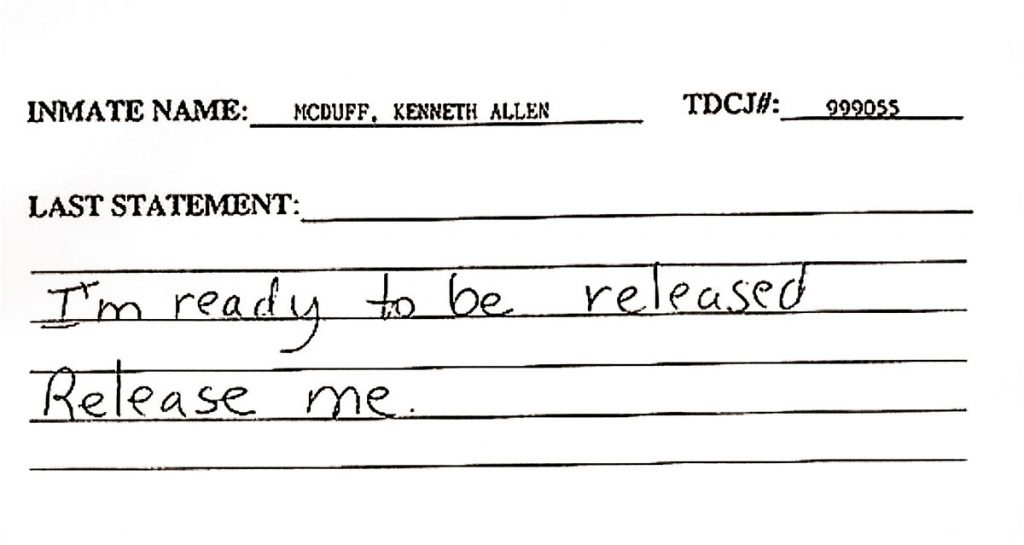

Caveng’s installation provokes in this sphere of tenseness a complete silence, a silence which is broken only by the death candidates’ last words. But here also a speechlessness determines the overly formulated statements. While Joseph Beuys interpreted food in the sense of transubstantiation as a sign of energy and nutritional value, Cavengs places the fruits and yoghurt and t-bone steaks in a actual endgame. The intensive power of “Final Meals” comes from its lucidity and cool calmness. From the wish of the last meal, whose ingredients are listed on the protocol, the artist has staged a posthumous portrait which remains with all of its empathy neither on one side or the other and which avoids emotionality as well as intense sorrow. The tension between prison protocol and the visualized last meal leads to stories which are far afield from the Boulevard press or prejudiced opinions, which deliver up either the good or the bad. In this irritating blending of life and death, of nourishment and consumption – including art-consumption – Caveng lets the observer make a picture with the pure facts alone.

download > memento mori vice versa |catalogue text by Michaela Nolte

download > catalogue text by Inge Herold at Hector Kunstpreis |Kunstalle Mannheim (german language)